Translation of text:

Recently Roses (came)

as a gift of the Pope,

although in cruel winter,

to you, heavenly Virgin.

Dutifully and blessedly is dedicated

(to you) a temple of magnificient design.

May they together be perpetual ornaments.

Today the Vicar

of Jesus Christ and Peter’s

successor, Eugenius,

this same most spacious

sacred temple with his hands

and with holy waters

he is worthy to concecrate.

Therefore, gracious mother

and daughter of your offspring,

Virgin, ornament of virgins,

your Florence’s people

devoutly pray

so that together with all mankind,

with mind and body, their entreaties may

move you.

Through your prayer,

your anguish and merits,

may (the people) deserver to receive of the Lord,

born of you according to the flesh,

the benefits of grace

and the remission of sins.

Amen.

Guillaume Dufay’s Motet Nuper rosarum flores was written for the consecration of the cathedral of Santa Maria del Florence, Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore (English translation: Basilica of Saint Mary of the Flower), on March 25, 1436. The event was monumental in that it was attended by Pope Eugene the IV, who made an offering of a golden rose, to decorate the high altar, a week before the consecration. Both of these events are mentioned in the text of the motet. It is noteworthy that it was very uncommon for the Pope to attend the dedication of a church.

Du Fay uses Terribilis est locus iste, an introit traditionally used for the consecration of churches, as the cantus firmus of his work. These words come from the Book of Genesis (Gen 28:17) and can be translated as “Awesome is this place.”

The piece is written for four voices and the sound is treble dominant, which is common for DuFay’s music. When viewing the score, the upper two voices are the only ones who sing the text. The phrases line up, more or less, at the start and end of each phrase.

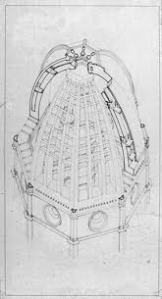

Du Fay based the music on elements of the church’s architecture. The dome of the church was designed by architect Filippo Brunelleschi who created the innovative double vaulted design of the cupola. It is believed that Dufay echoed this design in the lower two voices by having them sing the cantus firmus without words. This happens at four distinct times in the piece. The two lower voices are an octave and a fifth apart and their entrances are offset and rhythmically altered with no distinct diminution or augmentation that can quickly be detected. Eye witness accounts of the day’s ceremony state that there were many singers and instrumentalists performing which could suggest that the cantus firmus was played on instruments and/or the voices were doubled by them. The following link is a performance where the cantus firmus is played by organ. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JOkf_wxIcfQ

The word “Successor” stands out a great deal because of Du Fay’s use of canonic imitation in the upper two voices and the stark use of an open perfect 5th, between all four voices, at that point in the music. The following word “Eugenius” is given additional attention through homorhythmic scoring, again in the top two voices. This is the first time in the piece where the voices sing the same rhythm on the same word. The effect is very strong and, aside from Du Fay’s obvious attempt at impressing the Pope, a good indication that variety is a must in good music. The only other place where there is an almost (with some variety) unified rhythmic treatment of a word, this time with all four voices, is at the very end with the word “Amen.”

There is a great deal of structure to Du Fay’s work here. Each phrase has 7 syllables, an obvious nod to the use of the number 7 in the bible.

If the entire piece were to be divided into four parts, each section begins with the upper two voices and is eventually accompanied by the cantus firmus which continues until the final cadence of these sections. In the score each section is represented by 28 measures. Each section is broken into 14 measures of just the upper voices followed by 14 measures with cantus firmus. The duration of each section, however, varies based on their time signatures. If a constant tempo is assumed and the time signatures of the cantus firmus are reduced to having a common denominator then we can see these as being 12/4, 8/4, 4/4, 6/4 or a ratio of 6:4:2:3. This ratio reflects the proportions of the cathedral itself.

These last observations could be seen more as a theoretical analysis than something appropriate for a listening blog. This undoubtedly raises the question “can such organization be depicted aurally?” Whether some people have the ability to hear such things is debatable. Regardless, it is my opinion that every bit of detail that goes into the organization of music has a profound effect on the final product, the sound. It also gives a glimpse into the high level of craftsmanship possessed by these composers which, in my opinion, is so often missing in compositions today, often under the guise of “I just write what I hear.” Wouldn’t it be nice to have composers today give the same devotion to their audience as Du Fay did his, whether it was the church, the Pope, or just the people in attendance for the consecration of this place of worship?

You do a great job of connecting the more abstract, theoretical concerns of the piece with their real-world significance. The 6:4:2:3 ratio certainly has an effect on the way the piece sounds, even if listeners can’t immediately detect its proportions. Perhaps more importantly, the piece offers many possible significances (as you noted, the number 7 and the convergence of voices on “Eugenius”) for latter-day music scholars to discover and interpret, and that may be as important as the sonic impact of Du Fay’s music to his contemporary listeners. I’m curious to know whether you think there are any composers/musicians today who satisfy the criteria you pose in your final question. Hopefully your classmates will weigh in on this important question, too.